Not a Failure but a Feature ✨

Conflict, Collaboration, and Leaning into What Drives Us

Systems Design Lab helps social sector organizations use systems thinking and human-centered design to collaborate, innovate, and amplify their community impact. We work with technical tools, but we focus most on people. We are really good at bringing together diverse perspectives to make radical changes that lead to radical social change.

We’re having a session about motivation and conflict next week. Join us on May 21 at 12 pm ET for Why They Do That (and Why You Do, Too): A Real-Talk Session on Relationship Intelligence.

TL;DR // Conflict is inevitable in any collaborative effort. At SDL, we’ve been learning how to make conflict more generative by explicitly naming and drawing on the different motivations that bring us each into the work. We’re in an ongoing learning process that uses tools like the Strengths Deployment Inventory (SDI) to make sense of what goes wrong and to reinforce what goes right.

In an interview with scholar and writer Eve L. Ewing, organizer Mariame Kaba said that “everything worthwhile is done with other people.” At SDL, there’s nothing that gets us more excited than working with folks to nurture communities of creative courage and collective action. As Emma wrote in her previous post, we’re all in for fluid, trust-based, and relational approaches to systems change. After years of supporting these kinds of efforts, we’ve also developed a special interest in one of the most fundamental aspects of cultivating authentic relationships: conflict. We know it’s not an if; it’s not even a when. It’s a how: how do we frame conflict so that we don’t run away from it (and, inevitably only make it worse)? How do we get more skillful at it so that we can, as adrienne maree brown said, “embrace tension, [but not] indulge drama”? And how do we learn from it so that it builds our relational trust and our capacity to do good work together?

One of the tools we’ve been reflecting on is the Strengths Deployment Inventory (SDI). The SDI is an assessment that gives you three views of yourself: your motives, your strengths, and your conflict sequence. While yes, SDI aims to describe pieces of “you,” the power of the model is less about an individual profile and more about how it comes into relationship (and therefore conflict) with others.’ I have stories to tell about all three, but wanted to start off by sharing how Emma, Ke, and I have seen our collaboration both sharpened and muddled by our motives…and how we’re learning along the way.

Cliff’s Notes on SDI Motives

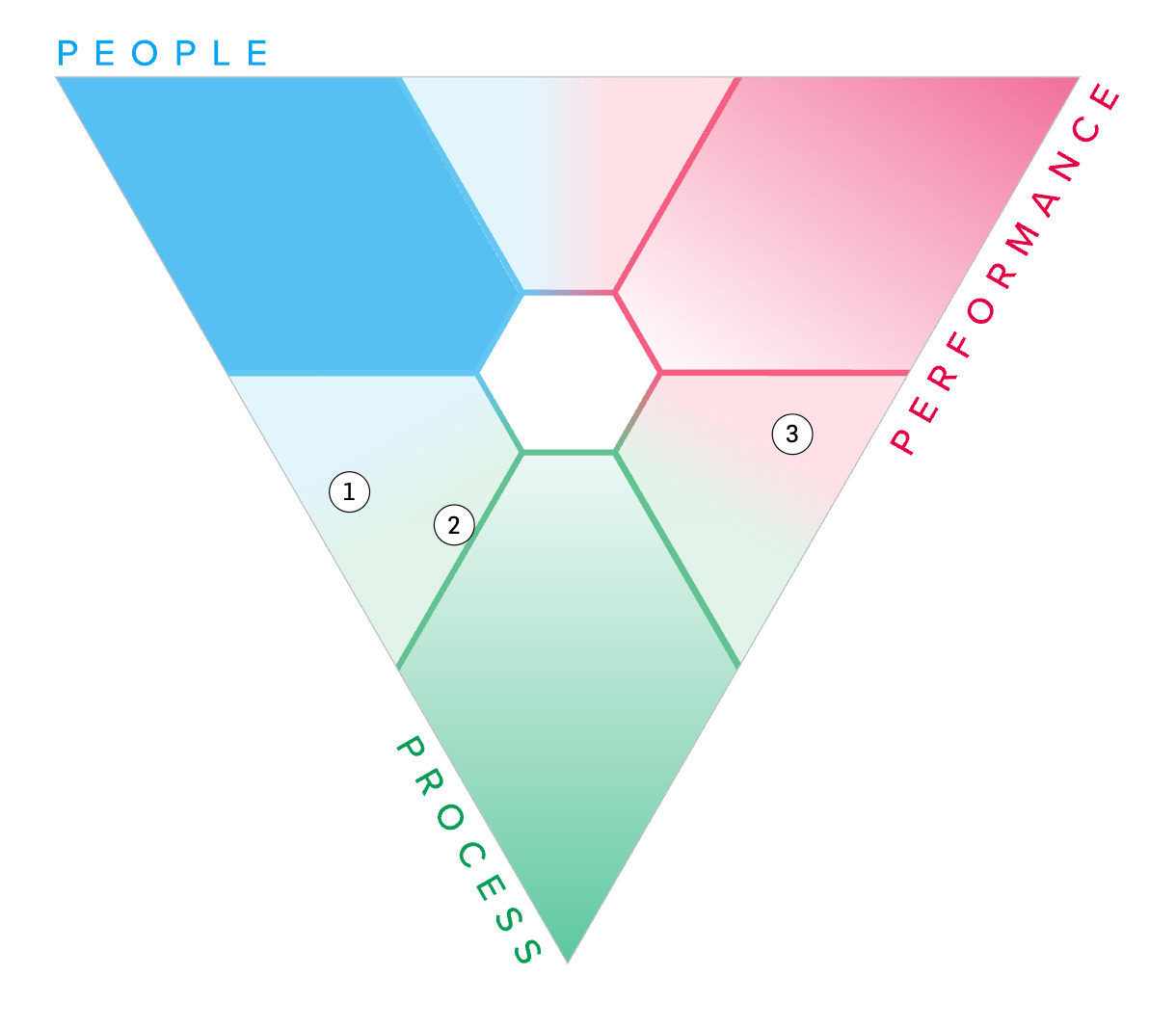

As a quick guide, SDI outlines three primary motives: People (Blue), Performance (Red), and Process (Green). We all have a combination of the three (we all want to help people, we all want things to make sense, and we all want to accomplish our goals); we just differ in the degree to which these motives drive us. When you take the SDI assessment, you’re placed somewhere in the tri-color triangle. Depending on where you land, you may be solidly one motive or a combination of two. A number of people will even fall squarely in the middle.

On our team, Emma and I share a motive profile: we are both Blue-Green (People-Process) people. This means we have a “strong desire to analyze the needs of others and to help others help themselves.” Ke is on the other side of the triangle. She’s a Red-Green (Performance-Process) person, meaning that she has a “strong desire to develop strategy and assess risks and opportunities.” In short, Emma and I love thinking about how to design processes that support people to be their best selves. Ke loves thinking about how to make strategic decisions that will get us to our desired outcomes rationally and efficiently.

When Things Are Going Well

Taking the SDI was one of the first things I did when I started at SDL (prompting lots of confusion for my parents about which three-letter S-acronym I worked at). Since that moment, motives have been a recurrent framework in our collaboration. We’ll have explicit conversations about it in our design and planning. Are we facilitating a session in which we want folks to feel like they have the space to play with new concepts? Emma is a good fit for that one. Is there a point during the day in which folks will need to make a critical decision? Time to tap Ke in. By naming and leaning into our natural orientations, we’re better positioned to approach complex work in a way that feels more easeful without over-simplifying what we’re trying to accomplish. There’s a release in trusting that you don’t have to hold it all and that your team will pick up on what you will inevitably miss.

You may be thinking “Ok, ok, but it can’t always work that well.” You would be right.

When We Muddled

Last year, we did something for the first time: we co-designed an agenda for a multi-day event as a trio. This event would launch a multi-month collaboration among a diverse set of stakeholders working in different parts of a large system. Our objectives were to not only start building trust among the folks in the room but also to get them to align around shared definitions and to agree on specific actions they would take in the following months. Oof, that’s a lot to strive for! In the lead-up to this event, we had each been tackling a piece of the puzzle that we were eager to bring to the team.

Emma had been holding project management and agenda creation and had a special interest in a section that felt critical to get folks on the same page around the problem they were working on. I had been analyzing preliminary data from participants and wanted to discuss how the potential variation in the room might impact some of our objectives and facilitation moves. Ke had been sitting with the action planning piece and wanted to know what people would be coming in with so that she could strategize her moves. All of these felt important. They were! So we brought them all into the meeting.

At a deeper level, how we each felt we wanted to tackle these questions was rooted in our motives. Emma and I (People-Process) each wanted clarity about a particular sequence of events and the possible dynamics we might design for. Ke (Performance-Process) needed to have a high-level understanding of the problem in order to make pointed decisions.

What was supposed to be a “quick review” of the agenda turned into 1.5 hours of muddling. Emma diagrammed and re-diagrammed her section, trying to respond to different. I pulled out more and more examples and played out different scenarios. Ke went quiet for a while before saying she didn’t totally understand what we were doing. We may have made some progress, but left feeling confused…and kind of crummy.

Over the next couple of hours, we each had the same a-ha: we had inadvertently walked into conflict because we hadn’t articulated to each other (and really to ourselves) how we were trying to address our core motives in the conversation. At different points, we felt a misalignment between where the conversation was going and where we thought it should go; in our own ways, we kept trying to remedy the situation without explicitly naming the conflict. All of our best efforts only dug us in deeper. This realization came with a sigh of relief: that made so much sense! What had been inscrutable in the moment became obvious with a little bit of breathing time.

Learning from and Leaning Into Our Mistakes

The next morning, we met, debriefed, and laughed it out. We were each honest about what it was that we were looking for, what had our conflict gears turning, and how we had (with the best of intentions!) contributed to us getting stuck. We could then turn to learning about this small misadventure.

Having identified the pieces that led to conflict, we could use this to strategize how to design differently moving forward: when do we need to have all hands on deck? What critical conversations should happen early on, and which are best left to individuals? What level of detail do we need at different points? We realized that it might be productive to have a Blue-Green sandwich: to have a three-way conversation in which Ke helps us get clear about our objectives and critical moves, send Emma and I off to think through and iterate on specifics, and then bring Ke back in to push on where we landed. We’re gearing up to test this new structure in a couple of weeks. I’m excited to see what goes differently now that we have a better idea of what (not) to do.

When I think about the fact that this muddling meeting came years into working well together (and teaching other folks about using SDI to strengthen their relationships), I’m reminded of Zen Master Dogen Zenji’s quote calling life “one continuous mistake.” Along the same line, meditation teacher Jessica Morey uses the phrase “of course”:

Of course doing something for the first time is hard!

Of course we we would lean into our natural orientations!

Of course we would try really hard to make things better!

These framings, like adrienne maree brown’s “never a failure; always a lesson” help naturalize and de-fangle conflict. Because it’s something we’ll have to practice with again (and again). Conflict happens when you bring people together and ask them to bring their whole selves. All we can aspire to is to be a little more skillful in the moment so we can breathe, laugh, and get creative together quicker.

» Want to learn more about SDI and relational intelligence? Join us on May 21st at 12 pm EST. You’ll get a chance to hear more about SDI and to play with using it in your own context.

» Beyond Sticky Notes pulled together a bunch of tools they’ve used to support processes of co-production and co-design

» Bad Bunny’s Baile Inolvidable video is a love letter to one of my favorite ways to feel in community: dance.

» Need a quick energy shift? Try using breath of joy.

Find us elsewhere: